What Lurks in the Deep?

In which the author admits that her thinking isn't always scientific.

I grew up near the ocean and spent a lot of time on the beach as a child. After powerful winter storms, the remains of dead animals would often wash ashore, and I loved to drag these half-rotted, half-eaten blobs home with me, so I could get a better look – hurray, science! Fins, skulls, fleshy bits of things tossed up from the briny deep… oh, my poor patient parents. In retrospect, our yard probably smelled pretty bad. Most were so decomposed that you were never certain what it had been in life. But in death, they became marvelous beasts of the imagination!

Then, I heard the story of Cadborosaurus. A cryptid living in front of my house?! Suddenly, every dogfish carcass, skate spine and crab claw became the puzzle piece of a gigantic monster – no longer science, but still, hurray!

Cadborosaurus, also affectionately known as Caddy, is a sea serpent that reputedly lives in the waters of the Salish Sea, and is named after Cadboro Bay, near Victoria, BC. Witnesses claim it resembles a snake with a horse-like head and long flexible neck, front flippers and a large fan-like tail. A similar creature appears in First Nations mythology all along the West Coast -- from Monterey Bay in California to the rocky fjords of Alaska -- and they have names like hiyitl'iik, t'chain-ko, and numkse lee kwala. Early European settlers added a few extra names to the mix, too, like ‘Klematosaurus’ and (my personal favorite), ‘Sarah the Sea Hag’.

Maybe it's not as famous as Nessie or Ogopogo, but Caddy has been spotted over 200 times in the last century. It was reportedly filmed in 2009 by a fisherman named Kelly Nash. It was even captured and released, twice — a 2-foot-long baby Cadborosaurus caught in 1968 off the coast of DeCourcy Island, and then another tiny version in 1991, in the San Juan Islands.

Stinky rotten remains, washed ashore, have also been labelled as Caddy -- although most of these were eventually identified as decomposed whales, sharks, or sea lions. The best physical example: a 3.2-metre-long something extracted from the belly of a sperm whale at the Naden Harbour whaling station in Haida Gwaii in July of 1937. The workers described its head as ‘a dog with the nose of a camel’, and they took a photo of the remains, which shows a snake-like form and a short, feathered tail.

What, exactly, could Caddy be?

Well, there's a few theories, some scientific, and some a bit more fanciful. The baby Cadborosauruses were most likely pipefish, a relative of the sea horse that lives in Pacific Northwest waters. They have long, thin bodies and they aren't the strongest swimmers, so they hang out in eel-grass beds which provide the perfect camouflage. They do look like miniature sea-serpents.

Another possibility could be a Pacific oarfish, also known as the giant oarfish or the king of herring. It's the world's longest bony fish, reaching lengths of up to 11 meters, and it has a ribbon-like shape with stubby fins and a small head. It lives a solitary life. It isn't often seen by people, but that doesn’t mean it’s rare or endangered -- it just keeps to itself in the upper levels of the ocean, quietly munching on krill and squid and smaller fish.

For those who want to be a little more speculative, the Elasmosaur is a handy possibility. During the Late Cretaceous period, Vancouver Island was submerged under a shallow sea, and these long-necked lizards cruised up and down the swampy coast. Today, their fossilized remains are found in river beds and shorelines. (One of the best displays of an elasmosaur is found at the Courtenay Museum, so if you want to see for yourself how impressive they were, drop by and bask in its shadow.) Elasmosaurs were the largest of the plesiosaurs, reaching 11 meters long and weighing 2.2 tons. They had a streamlined body with a small head, paddle-like limbs. and an extremely long and serpentine neck which reached up to 7 meters. They looked like the classic sea monster, so it's easy to link Elasmosaur and Cadborosaurs, except for the pesky fact that it's been extinct for 80 million years.

Plus, some paleontologists have speculated that the Elasmosaur was unable to lift its head above the surface of the water, given the immense weight of its incredibly long neck. It likely had limited musculature which would have restricted the movement of its head, and made it impossible for Elasmosaur to move its head side-to-side or up-and-down while it was moving forward. Many of the sightings say that Caddy's head is raised above the surface of the water, a feat that Elasmosaur might not have been able to accomplish.

No matter what Cadborosaurus' true nature, it's been spotted up and down the West Coast of North America for decades, maybe even centuries, and it provides a fascinating insight into how people explain the unfamiliar and react to the weird creatures that rise up from the ocean depths. Maybe Caddy's real, maybe it isn't, but either way, it's still makes for fascinating history!

And sightings of Caddy aren't relegated to the past. There's been lots of recent sightings, too, such as one that occurred in December 2006, when a giant snake-like creature was spotted only 40 meters off the coast of Victoria, and then spotted again 160 km farther north, at Qualicum Beach. It was sighted again in 2013 off the coast of Galiano Island, a 40-foot-long glossy black snake splashing in the shallows. The most recent sighting occurred in 2019, in calm water near Port Townsend, WA.

Caddy even has its own organization now, dedicated to finding and identifying the monster. CaddyScan is a Victoria-based group that collects and records sightings of Cadborosaurus, and they monitor cameras that have been set up at points along the BC Coast in an effort to capture high-quality video of the beast. They claim that there's 2 to 10 reported sightings each year, which doesn't sound like a lot given the size of the area they cover, but then again, there needs to be two elements to have a monster sighting – (1) the monster and (2) the witness. If there's no people around to spot and report, you can't have a sighting, and most of the BC coast is sparsely inhabited, which is perfect for mysterious cryptids who prefer their privacy.

Given the nature of the Circus Salmagundi mysteries, I’ve spent a lot of time in the last three years learning about West Coasts boats and shipwrecks, maritime superstitions and nautical mayhem. Will Cadborosaurus make an appearance in a future Circus Salmagundi mystery? Let’s look at the facts… nothing is more exciting that a monster lurking in the deep. I think the answer to that question is a very scientific, YES.

****

Book notes:

I’ll be at the Parksville Summer-by-the-Sea market on July 9, from 6pm to 9pm, and I hope you’ll drop by my booth to say hello! I have a limited number of titles to sell, but you’ll certainly find a mystery or two suitable for summertime reading.

I’ll also be popping up at the Comox Valley Makers Market on July 20, from 10 am to 2:30 pm, at the Old Farm Market, 660 England Ave in Courtenay. See you there!

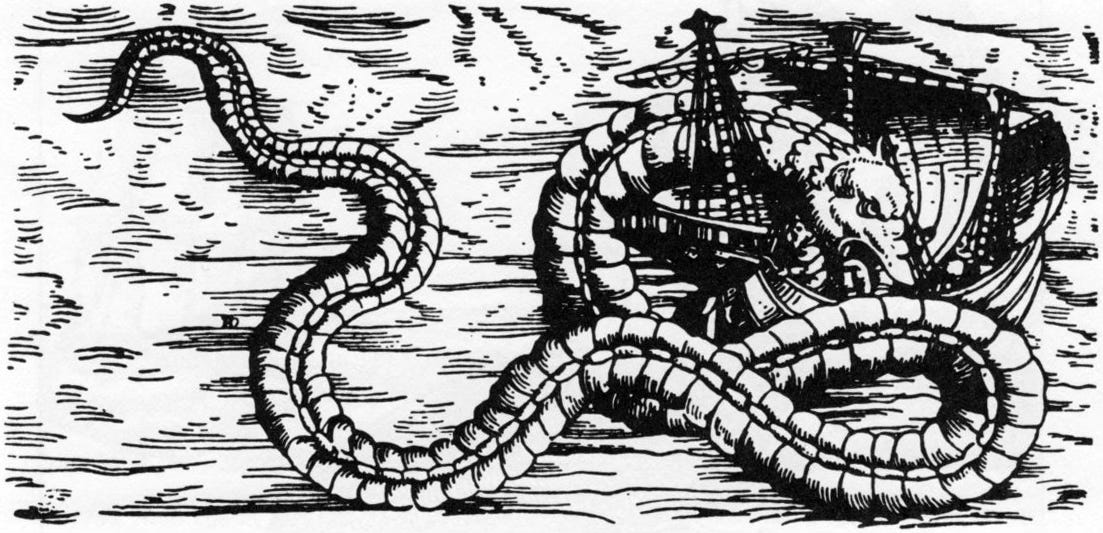

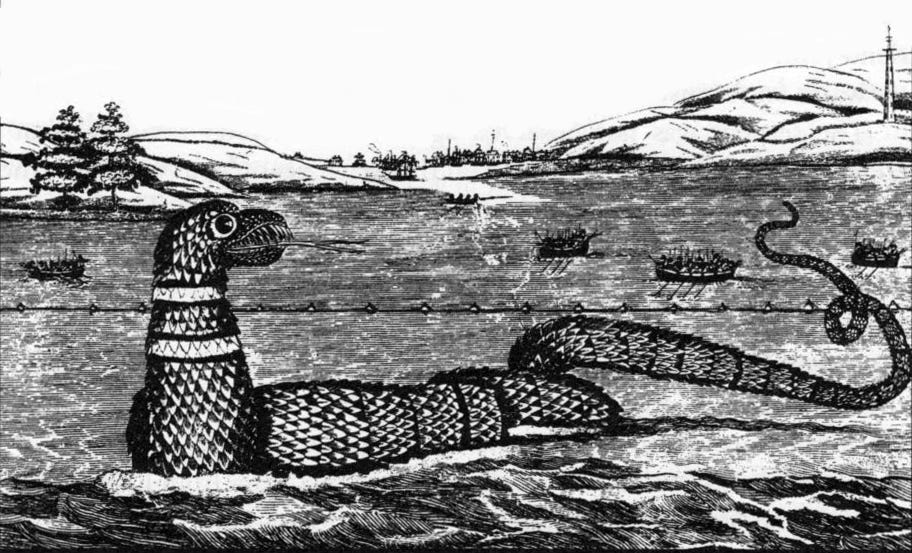

In the pursuit of historical accuracy, I feel I must explain that first picture above is the ‘Sea Orm’ from 1555 and the second is of the ‘Gloucester Sea Serpent’ of 1817. Cadborosaurus deserves its own enigmatic woodcut illlustration, I think… I might have to doodle around with the idea.

If you’re flying in and out of the Comox Airport YQQ, you’ll find copies of ‘Truly the Devil’s Work’ in the gift shop. Probably the right length to entertain for a five- to eight-hour flight?